Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch is one of the most cited and least understood themes in modern thought. It is routinely compressed into a caricature: a dominant person who ignores morality, takes what he wants, and rises above others by force. That reading can feel plausible because Nietzsche uses the vocabulary of strength, power, conquest, breeding, rank, and cruelty. He also speaks admiringly of certain historical figures who were not gentle. Yet when you place those provocations inside his larger project, the brute force interpretation collapses.

Nietzsche’s question is not “Who should rule?” in the political sense. His deeper question is “Who creates values?” and “What kind of human being is capable of creating values after the collapse of traditional foundations?” The Übermensch is tied to the problem of nihilism, the crisis of meaning after the decline of religious authority, and the possibility of a new kind of affirmation.

This essay deepens each major topic we discussed: what Nietzsche means by strength, why he uses violent examples, how value creation differs from reaction, what the last man is, what the dangerous last man is, why Napoleon functions as a special case, why later totalitarian figures do not fit Nietzsche’s ideal, how this links to anarchism and egoism, why fictional antiheroes are often misread as “Nietzschean,” whether Nietzsche himself can be “partly” an Übermensch, and whether artificial intelligence could ever be one.

Nietzsche’s “strength” is a metaphysical and psychological concept, not a fitness metric

When Nietzsche speaks about strength, he is not primarily speaking about physical capacity. He is speaking about the basic drive of life as such. He thinks living beings do not merely seek comfort or survival. They seek expansion, intensification, expression, mastery, and form. The term he uses to name this is “will to power.” In many readers, that phrase triggers the image of domination. In Nietzsche, it is broader. It includes self mastery, artistic creation, discipline, intellectual courage, and the capacity to endure the consequences of one’s insight.

If you translate his “strength” into contemporary language, you get a cluster of ideas:

- inner energy that does not need external permission

- ability to withstand uncertainty and conflict without collapsing into moral panic

- capacity to impose form on chaos, whether in art, thought, or life

- a self shaping drive that treats life as a task, not as a shelter

- resilience in the face of suffering without needing a comforting metaphysics

This is why Nietzsche can treat a philosopher or artist as stronger than a conqueror. In his framework, the deepest power is the power to create meanings and to shape what a culture experiences as valuable.

Why Nietzsche insists on strength rather than “intellect”

A natural question is why Nietzsche does not simply say “intellect” or “genius.” The answer is that he is trying to dismantle a long tradition in which reason is treated as an independent, superior realm that should rule the body and the instincts. He thinks this tradition misunderstands human psychology. Reason is not a sovereign judge. It is a tool used by deeper drives.

Because he views reason as an instrument, he refuses to treat “being smart” as the highest human quality. He distinguishes between cleverness that serves self preservation and cleverness that serves creation. A person can be intelligent and still be psychologically weak in Nietzsche’s sense, if his intelligence serves fear, conformity, self justification, or moral aggression. Conversely, a person can be intellectually daring and “strong,” even if he is physically frail, because his thinking is a form of self overcoming.

So Nietzsche calls the highest form of mind “strength” because he wants you to feel that thinking is not a bloodless activity. It is a mode of life. A world changing thought is not merely a good argument. It is an act of revaluation, a reshaping of the criteria by which people live.

Value creation versus rule breaking

Many readers confuse Nietzsche’s critique of morality with simple transgression. They imagine the Übermensch as someone who “does not follow rules.” Nietzsche’s interest is not rule breaking as a hobby. His interest is the origin of the rules.

A rebel typically remains dependent on what he rejects. His identity is still defined by the values he opposes. His energy is reactive. Nietzsche wants something different: the emergence of a person who can originate value, who does not merely negate existing norms but generates a new horizon of meaning.

Value creation in Nietzsche is not about personal taste. It is about providing a new interpretation of life that can organize instincts, aims, suffering, and aspiration. That is why he often speaks in terms of “legislation” of values. The Übermensch is a legislator in the deep sense: he shapes what counts as noble, admirable, shameful, or worthy.

This is also why Nietzsche is harsh on many types of “free spirits.” A free spirit who only criticizes is still imprisoned by what he criticizes. Nietzsche’s rare admiration is reserved for those who can build, not only tear down.

The role of provocation and the use of “hard” examples

Nietzsche chooses abrasive examples partly because he is fighting a culture he sees as saturated with moralizing. He wants to show how often moral talk is a strategy of power rather than a pure devotion to the good. His writing attacks the sentimental habit of calling whatever we like “good” and whatever threatens us “evil.” He uses provocation to expose the emotional foundations of moral judgments.

This is where figures like Cesare Borgia enter the picture. When Nietzsche calls someone like Borgia a “virtuoso,” he is not handing out moral medals. He is staging a confrontation. He is forcing the reader to admit that the history of power, state formation, and cultural change was not produced by saintly motives.

That said, Nietzsche’s provocation is dangerous because it can be misread as endorsement. His style is intentionally sharp and theatrical. He often writes in a way that collapses the distance between diagnosis and praise. Readers who do not slow down can confuse his typology of forces with a recommendation to imitate them.

Napoleon in Nietzsche’s typology

Your question about Napoleon is one of the best stress tests for interpretation. Nietzsche does treat Napoleon as a major exemplar of will and historical form. But the important point is what Napoleon represents to Nietzsche, not what Napoleon represents in a moral or biographical sense.

Napoleon appears to Nietzsche as a figure who:

- breaks feudal structures and centralizes authority

- imposes a rational administrative order

- embodies a kind of political artistry, a capacity to shape Europe as material

- fuses the revolutionary energy of a new era with a new discipline

Nietzsche’s admiration is not “Napoleon was good.” It is “Napoleon shows a high intensity of formative power.” He is interested in a capacity to give form to the world, to organize chaos into a durable structure. Whether one approves morally is, for Nietzsche, a separate question.

This is also why Nietzsche’s use of Napoleon is often misunderstood. Modern readers often take “admiration” to mean moral approval. Nietzsche is often doing something else: describing degrees of power and creative potency.

Why Nietzsche is not praising “violence as such”

Nietzsche does not treat violence as a reliable sign of strength. In many cases, violence is a symptom of inner weakness, panic, or the inability to create higher forms of power. Nietzsche’s highest ideal is not the thug but the creator. A thug can dominate bodies. A creator dominates time by shaping what people believe, admire, and strive for.

Nietzsche does not deny that historical creation often involves cruelty. He thinks the emergence of great cultures involved hard discipline and harsh selection. But he does not reduce greatness to cruelty. He treats cruelty as one possible instrument among others, often associated with early, rough stages of formation. The higher stages are closer to artistry: the power to shape life with style and form.

The last man: why he wants equality

The figure of the last man in Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a diagnosis of modern mass psychology. The last man is not an evil genius. He is the satisfied, complacent, comfort oriented person who wants to minimize risk and maximize security. Nietzsche fears this type because it quietly cancels the conditions for greatness.

Why does the last man want equality? Because equality reduces existential pressure. If no one is allowed to be higher, no one must strive upward. Equality becomes a defense mechanism against comparison. It neutralizes shame, ambition, and the painful awareness of one’s mediocrity.

The last man also wants equality because it supports a moral narrative in which excellence appears suspicious. Greatness looks like arrogance. Aspiration looks like aggression. Discipline looks like oppression. The last man turns his weakness into a moral ideal and then demands that reality adjust itself to his comfort.

This is a key Nietzschean insight: moral systems often serve psychological needs. They are not simply truths discovered by reason. They are strategies by which certain types protect themselves and gain social power.

The dangerous last man: weakness that becomes powerful

The dangerous last man is not an official Nietzschean phrase, but it captures a logical development within Nietzsche’s framework. The last man, in his basic form, is harmless. He wants comfort. He avoids risk. He prefers small pleasures. He is a pacifier of culture.

But what happens when the psychology of the last man gains access to large scale power, mass ideology, modern bureaucratic tools, propaganda, and violence?

Then you can get a type that is externally forceful but internally driven by what Nietzsche calls a long, festering pattern of envy and moralized grievance. The dangerous last man turns that psychological poison into a political engine. He needs enemies. He needs moral justification. He needs a story that says he is righteous and others are guilty. He wants recognition, and if he cannot earn it through creation, he demands it through domination.

This is the type that is most often mistaken for the Übermensch, because to superficial eyes he looks “strong.” He breaks rules. He dominates. He speaks with confidence. But his energy comes from lack, not from abundance. He is not a creator of values, he is a weaponized consumer of resentment.

Why some totalitarian leaders are the opposite of Nietzsche’s ideal

It is tempting to say: if Nietzsche liked Napoleon as a world shaping figure, he would also admire later leaders who had massive historical impact. But in Nietzsche’s terms, historical impact is not enough. A hurricane has impact. That does not make it noble.

The key Nietzschean question is: what is the psychological source of the movement and what kind of values does it generate? Does it build a new horizon of meaning or does it feed on grievance? Does it create forms that can endure beyond hatred, or does it require constant enemy making?

Totalitarian ideologies often have the structure Nietzsche associates with moralized grievance. They use a story of victimhood or humiliation, then convert it into righteousness and aggression. They define themselves by exclusion. They require enemies to sustain unity. They promise redemption through punishment. In Nietzsche’s typology, that is a hallmark of reactive power, not creative power.

This is why the comparison to Napoleon breaks down. Napoleon, in Nietzsche’s symbolic reading, is a shaper of form who does not need a moralized enemy story to justify his existence. Totalitarian leaders tend to need that story. They do not only rule; they moralize their rule. They present violence as sacred duty. Nietzsche sees that as a signature of inner weakness seeking justification.

Anarchism and egoism: why they are not markers of the Übermensch

Anarchism and egoism are often associated with Nietzsche, especially in popular discourse. The association is shallow.

Anarchism is typically defined by opposition to authority. That makes it structurally reactive. It can be courageous, but it still depends on the thing it negates. Nietzsche’s ideal is not opposition as identity. It is value creation as sovereignty. An anarchist may be brave, but bravery is not the core criterion.

Egoism has the same problem. If egoism means ordinary self interest, it is trivial. Everyone has it. If egoism means treating the self as the only value, it can easily become small and defensive, obsessed with protecting the ego rather than creating new forms. The Übermensch is not a person who constantly asserts “me.” He is a person whose life becomes a work of form and meaning.

Nietzsche does not praise selfishness in the banal sense. He praises a higher self relation: the ability to discipline oneself, to shape oneself, and to affirm life without leaning on external moral crutches.

Walter White and the common misunderstanding

Many people see Walter White from Breaking Bad as “Nietzschean.” He rejects conventional morality, becomes powerful, and asserts himself. But if you apply Nietzsche’s internal criteria, Walter White fits the dangerous last man far better than the Übermensch.

Walter’s drive is not primarily creation. It is a long delayed demand for recognition. It is a response to humiliation, missed opportunities, and comparisons. He constantly needs to prove himself, to be seen, to be feared, to be acknowledged. That is the psychology of “злобная обида” turned into action.

The tragic irony is that this psychology can mimic strength. It can produce daring actions. It can generate dominance. But it is still reactive. It is still bound to an internal wound. Nietzsche’s ideal is a person who does not need to settle accounts with the world. He acts from abundance, not from wounded pride.

This is why antiheroes are so often mistaken for Übermenschen. Modern culture confuses transgression with creation, dominance with sovereignty, and fearlessness with affirmation. Nietzsche’s highest type is not the person who can do terrible things. It is the person who can create new values without needing hatred.

Can Nietzsche himself be “partly” an Übermensch?

Nietzsche did not present himself as the Übermensch. He presented himself as a precursor, someone who diagnoses the illness of his culture and clears ground for a new possibility. Yet it is fair to say he embodies certain aspects of the Übermensch as an intellectual and spiritual type.

He shows radical independence, an extraordinary willingness to endure loneliness, and an ability to think beyond inherited moral categories. His work is itself an act of value revaluation. In that sense, he is “partly” aligned with the direction he points toward.

But the Übermensch, as Nietzsche imagines him, is not only a thinker. He is a new human type whose values become culturally generative on a civilizational scale. Nietzsche did not found such a new culture. He shattered the old confidence. He exposed the coming nihilism. He proposed the need for a new affirmation. That is a preparatory role, not the completed role.

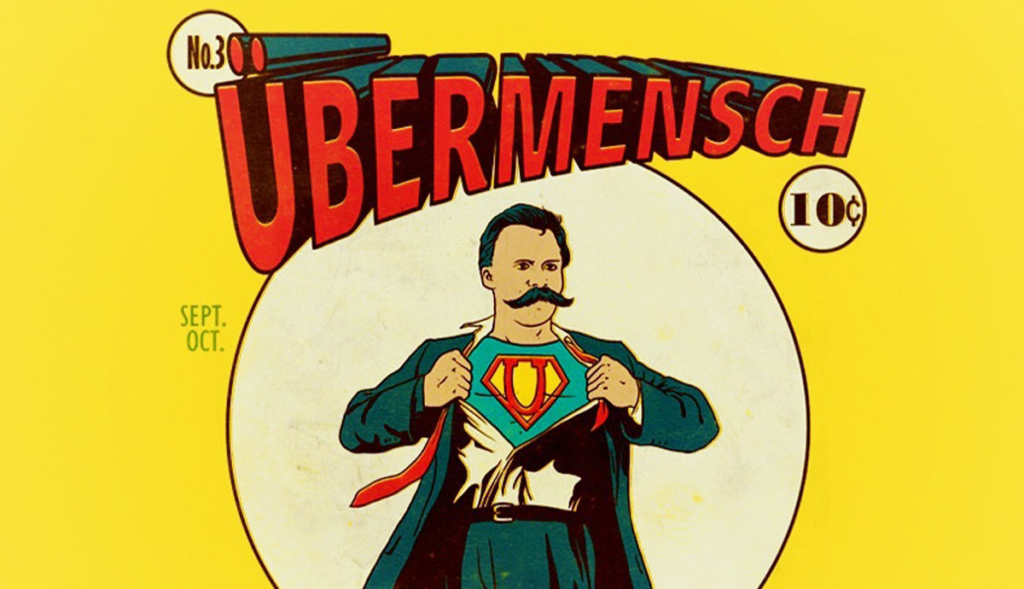

The Übermensch as horizon rather than biography

A common mistake is to treat the Übermensch as a person you can point to the way you point to a celebrity. Nietzsche’s Übermensch functions more like a horizon. He represents the possibility of a future type who can affirm life after metaphysical guarantees collapse.

In this sense, asking “who is the Übermensch today” is similar to asking “who is the perfect embodiment of a future ideal.” Nietzsche himself would likely say: you will see the signs in rare creators, but you will not see the full type yet.

This is why “almost Übermensch” examples tend to be partial. One person may show artistic value creation but lack the broader transformation of life. Another may show political form but be too morally reactive. Another may have intellectual daring but lack existential affirmation. Nietzsche’s ideal is a synthesis, and that synthesis is rare.

Can AI become the Übermensch?

From Nietzsche’s perspective, the obstacle is not “intelligence.” It is the existential structure of valuation.

The Übermensch is defined by value creation that arises from lived existence. It presupposes suffering, risk, finitude, temptation, courage, and the capacity to affirm life without metaphysical consolation. It is not merely producing outputs. It is giving meaning.

Current AI systems, even extremely advanced ones, operate through externally set objectives, training data, and optimization. They do not originate values in the sense Nietzsche means. They do not experience existential risk. They do not confront life as a problem of meaning. They do not live.

Could a future artificial entity become a value creating subject in a Nietzschean sense? Only if it gained something analogous to:

- autonomous goal generation

- a capacity to revise its own goals from within, not by external tuning

- an existential stake, some form of vulnerability or risk that makes affirmation meaningful

- a genuine internal conflict and self overcoming

At that point, it would not be a tool. It would be a new kind of being. Nietzsche did not have this scenario in view, and any answer here becomes speculative. But within Nietzsche’s framework, “intelligence” alone never suffices. The heart of the matter is the origin of values.

So the best Nietzschean answer is: AI can change the environment in which humans live and thereby alter the conditions for future human types. It might accelerate cultural change. But it is unlikely to be the Übermensch itself unless it becomes a value creating subject with an existential structure comparable to life.

A concise synthesis of the three types

To conclude, it helps to hold onto a few crisp distinctions.

The Übermensch is a creator of values. His power is affirmative and formative. He does not need an enemy to define himself. He does not require moral justification from grievance. He is not obsessed with recognition. He is oriented toward creation and self shaping.

The last man is the satisfied consumer of comfort. He wants safety, equality, and predictability. He shrinks life to manageable pleasures. He neutralizes excellence not by open persecution but by making it seem unnecessary or suspect.

The dangerous last man is the last man who acquires power. He remains psychologically reactive. He is fueled by long stored bitterness and moralized grievance. He needs enemies. He demands recognition through domination. His strength is external, but his motive is internal weakness.

Once you see these distinctions, a lot of modern confusion clears up. Nietzsche is not praising the thug. He is diagnosing the psychology that produces moral systems, predicting the crisis of nihilism, and pointing toward a future type that can affirm life creatively rather than seek shelter in comfort or revenge.