Origins, Psychology, and Consequences

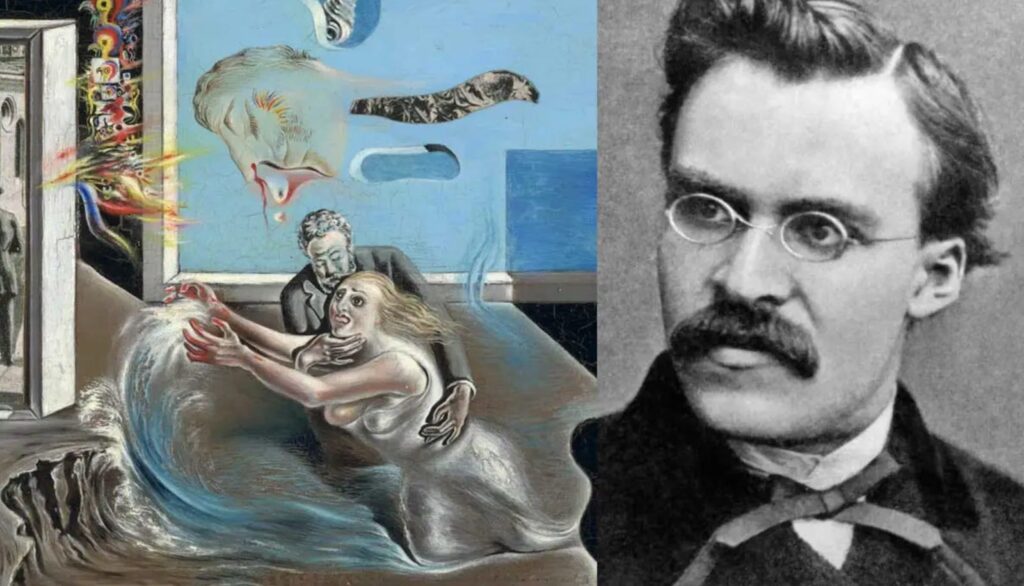

Nietzsche’s distinction between master morality and slave morality is one of the central analytical tools of his philosophy. It is often misunderstood as a crude social hierarchy or a literal division between rulers and the oppressed. In fact, Nietzsche is not offering a political program or a moral recommendation. He is describing two fundamentally different ways in which values come into existence. The distinction is genealogical and psychological, not legal or institutional.

Understanding this distinction is essential for grasping Nietzsche’s critique of morality, his diagnosis of nihilism, his fear of the “last man,” and his idea of the Übermensch. It also clarifies why Nietzsche admired certain historical figures, criticized egalitarian moral systems, and distrusted mass movements driven by grievance.

This essay explains master and slave morality in their original sense, shows how they arise, how they differ structurally, how slave morality becomes dominant in modern culture, and why Nietzsche thought this dominance was both historically understandable and spiritually dangerous.

Morality as a Human Creation

Nietzsche rejects the idea that moral values are timeless truths discovered by reason or given by God. For him, morality is a human creation, shaped by psychological needs, social conditions, and power relations. Moral concepts do not fall from the sky. They are invented, transformed, and enforced by particular types of people under particular conditions.

This does not mean morality is arbitrary. It means morality has a history. Nietzsche calls his method genealogy because he traces moral values back to the conditions that produced them. When he asks what good and evil mean, he asks who needed these meanings, when, and why.

Master morality and slave morality are two different answers to this question.

Master Morality: Values Born from Strength

Master morality arises among people who experience themselves as strong, secure, and self-affirming. This strength is not necessarily physical. It is psychological and existential. Such people feel at home in the world. They do not experience life as an accusation or a problem that needs justification.

In master morality, values originate directly from self-affirmation. The noble type experiences himself as good and calls his own qualities good. Strength, courage, generosity, pride, independence, self-confidence, and the capacity to command are seen as positive because they express life at a high intensity.

Crucially, master morality does not begin with hostility. It does not need an enemy in order to define itself. It does not say “we are good because others are evil.” It simply says “we are good,” and whatever contrasts with this goodness is experienced as lesser, inferior, or contemptible, but not morally evil in the later sense.

For Nietzsche, the original contrast in master morality is good versus bad, not good versus evil. “Bad” here means low, weak, common, or lacking distinction. It is a descriptive judgment, not a moral condemnation.

Master morality is affirmative. It begins with a “yes” to life, to oneself, and to one’s way of being.

Slave Morality: Values Born from Weakness

Slave morality arises under very different conditions. It emerges among people who experience themselves as weak, threatened, constrained, or dominated. These people cannot express their impulses directly. They cannot act out their aggression, ambition, or desire for power openly.

Over time, this blocked energy turns inward. It becomes a long-lasting, internalized hostility toward those who appear strong, confident, or independent. This hostility does not disappear. It is transformed.

Instead of acting, the weak evaluate. Instead of affirming themselves, they judge others. They create a moral framework in which the qualities of the strong are reinterpreted as evil, dangerous, sinful, or immoral.

Slave morality begins with negation. It does not say “we are good.” It says “they are evil,” and then defines goodness as whatever is opposite of the strong. Humility, obedience, patience, meekness, compassion, and equality become virtues, not because they express strength, but because they protect the weak and restrain the strong.

In this way, slave morality reverses the value structure of master morality. What was once admired becomes suspect. What was once contemptible becomes morally elevated.

The Role of Long-Term Grievance

A key psychological engine of slave morality is long-term, suppressed hostility. Nietzsche emphasizes that this hostility cannot be discharged directly. It accumulates. It becomes internal. It seeks an outlet.

The outlet is moralization. Moral condemnation allows the weak to feel superior without becoming strong. It allows them to judge, accuse, and symbolically punish those who threaten them, even if they cannot confront them directly.

This is why slave morality is deeply moralistic. It is concerned with blame, guilt, sin, and responsibility. It interprets suffering not as a fact of life but as evidence that someone is at fault.

Slave morality does not simply protect the weak. It also offers psychological compensation. It provides meaning to suffering by framing it as moral superiority. “We suffer because we are good. They prosper because they are evil.”

Christianity as the Historical Triumph of Slave Morality

Nietzsche sees Christianity as the most successful historical expression of slave morality. This is not because Christianity is false in a simple sense, but because of the type of values it elevates and the psychological needs it serves.

Christian morality glorifies humility, obedience, meekness, self-denial, and compassion for the suffering. It condemns pride, strength, ambition, and self-assertion. It reverses the aristocratic value structure of the ancient world.

For Nietzsche, this reversal was historically understandable. Christianity arose among socially and politically powerless groups. It offered dignity, meaning, and hope to those who lacked worldly power. It transformed weakness into a moral advantage.

However, Nietzsche argues that the long-term dominance of this value system has profound consequences. It trains humanity to distrust strength, to feel guilty for excellence, and to interpret life itself as something that must be justified or redeemed.

6. Moral Universalism and the Expansion of Slave Morality

One of the defining features of slave morality is its universalism. Master morality is local and particular. It applies to a specific group that sees itself as noble. Slave morality, by contrast, insists that its values apply to everyone.

This universalism serves an important function. If humility, equality, and self-denial are declared universal moral laws, then no one is allowed to rise above the moral level of the weak. The strong must be restrained, disciplined, or made to feel guilty.

Nietzsche sees modern egalitarian moral systems as secularized versions of this dynamic. Even when religious belief fades, the moral structure remains. Equality becomes sacred. Excellence becomes suspicious. Hierarchy is treated as injustice rather than as a natural expression of difference.

This is not simply a political critique. It is a psychological one. Nietzsche is describing how certain value systems function to manage anxiety, resentment, and fear of comparison.

Master Morality and the Creation of Culture

Nietzsche does not claim that master morality is morally “better” in an absolute sense. He claims that great cultures historically arise from value systems closer to master morality.

High art, philosophy, science, and state formation require long-term discipline, hierarchy of values, and the willingness to privilege excellence over comfort. These conditions are difficult to sustain in a culture dominated by slave morality, because such a culture is suspicious of distinction and allergic to suffering.

For Nietzsche, the danger is not compassion itself. It is compassion elevated into a supreme moral principle that overrides all other values. When the reduction of suffering becomes the highest good, life is gradually flattened. Risk, ambition, and greatness appear morally questionable.

The Last Man as the End Point of Slave Morality

The “last man” represents the final outcome of a society fully shaped by slave morality. He does not rage against the strong. He no longer needs to. The strong have already been neutralized.

The last man values comfort, safety, and small pleasures. He wants equality not out of hatred but out of fatigue. He wants a world without sharp edges, without danger, without great aspirations.

Slave morality initially arises from hostility. In the last man, it ends in complacency. The moral struggle disappears, but so does greatness. Life becomes manageable, predictable, and spiritually thin.

This is why Nietzsche feared the last man more than open tyrants. The last man does not persecute excellence. He renders it unnecessary.

The Dangerous Variant: When Slave Morality Gains Power

There is, however, another possible outcome. When the psychological structure of slave morality gains access to mass power, ideology, and violence, it can become destructive.

In this case, moralized grievance no longer remains internal. It turns outward. The world is divided into righteous victims and guilty enemies. Violence is justified as moral duty. Punishment is framed as justice.

This is the point at which slave morality becomes dangerous. It no longer restrains strength. It weaponizes weakness. It creates movements that are intensely moralistic, emotionally charged, and obsessed with identifying enemies.

Nietzsche saw this possibility long before the twentieth century. He understood that moral systems based on long-term grievance can become ruthless once they acquire the means to act.

Why Slave Morality Is Often Mistaken for Moral Progress

One reason Nietzsche’s critique is so controversial is that slave morality often presents itself as moral progress. It speaks the language of justice, equality, and compassion. These are powerful and emotionally persuasive values.

Nietzsche does not deny that these values can reduce suffering. His concern is different. He asks what kind of human beings are produced when these values become dominant and exclusive.

Does the culture encourage self-overcoming or self-protection? Does it cultivate creators or caretakers? Does it value excellence or safety above all else?

For Nietzsche, moral progress measured only by the reduction of suffering risks producing a humanity that no longer knows how to aim high.

The Übermensch Beyond Master and Slave Morality

The Übermensch is not a return to ancient master morality. Nietzsche is explicit about this. The Übermensch is a new type that emerges after the collapse of traditional moral frameworks.

He does not simply revive aristocratic values. He creates new ones. He affirms life without needing metaphysical guarantees or moralized enemies. He is neither a tyrant nor a moral preacher.

The Übermensch integrates strength with self-discipline, affirmation with responsibility, and creativity with endurance. He does not need to degrade others to feel valuable, and he does not need universal approval to act.

In this sense, the Übermensch stands beyond the historical conflict between master and slave morality. He resolves it not by compromise, but by transformation.

Why This Distinction Still Matters

Master and slave morality are not relics of ancient history. They are living psychological patterns. They shape debates about equality, justice, identity, power, and culture.

Nietzsche’s analysis remains unsettling because it challenges the assumption that moral language is always innocent. It invites us to ask uncomfortable questions about why we value what we value, and whose psychological needs those values serve.

This does not mean Nietzsche offers simple answers or easy replacements. His philosophy is diagnostic rather than prescriptive. He exposes tensions rather than resolving them.

Final Perspective

Master morality and slave morality are not labels for good people and bad people. They are descriptions of how values arise under different existential conditions.

Master morality begins with affirmation and creates values from strength. Slave morality begins with negation and creates values from long-term grievance. Both are human responses to life. Both have historical justification. But they lead cultures in very different directions.

Nietzsche’s warning is not against compassion or equality as such. It is against a civilization that allows only one moral register to exist, that cannot tolerate excellence without guilt, and that mistakes safety for meaning.

The enduring power of Nietzsche’s analysis lies in this question:

Are our values expressions of life’s fullness, or strategies for managing fear?

That question remains unresolved.