A Comparative Study of Ancient Greece and the Modern Western World

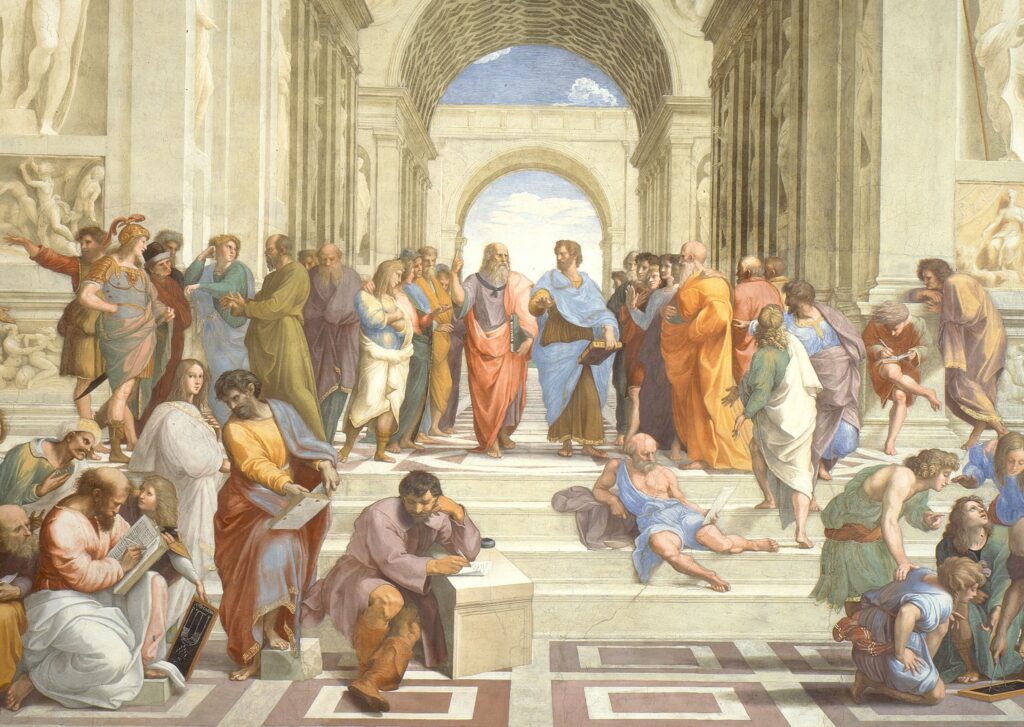

Philosophy originated in Ancient Greece as a distinctive mode of inquiry that combined rational investigation, ethical self formation, and a comprehensive vision of reality. Over the centuries this original orientation underwent profound transformations. In the modern Western world philosophy is largely practiced as an academic discipline, institutionalized within universities, professionalized, and often separated from everyday life. This article examines how the study, use, and general attitude toward philosophy differed between Ancient Greece and the modern Western world. It argues that these differences are not merely institutional but reflect deeper changes in the understanding of truth, knowledge, the human person, and the purpose of intellectual activity.

The comparison is organized around several core dimensions: the social role of philosophy, its aims, methods, institutional context, relationship to ethics and politics, and its practical significance for life. By tracing these contrasts, the article aims to clarify how philosophy shifted from a lived practice oriented toward wisdom to a specialized form of theoretical knowledge.

Philosophy in Ancient Greece: Origins and Cultural Context

In Ancient Greece philosophy emerged in a cultural environment that lacked rigid separation between intellectual, ethical, religious, and political life. The early Greek thinkers did not regard philosophy as one discipline among others but as a comprehensive search for truth about the cosmos and human existence. The term philosophia itself meant love of wisdom, not mastery of a technical field.

The earliest Greek philosophers, often called Presocratics, such as Thales, Anaximander, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, sought rational explanations of nature and being. Their inquiries were motivated by wonder, a sense that the world possesses an intelligible order accessible to human reason. These thinkers did not write for academic audiences but addressed a broader cultural community. Their work combined cosmology, metaphysics, and implicit ethical reflection.

Importantly, philosophy in this period was not sharply distinguished from what would later be called science, theology, or ethics. Inquiry into the structure of the cosmos was inseparable from reflection on the place of the human being within it. Knowledge was valued not as an end in itself but as a path toward understanding how one ought to live.

Philosophy as a Way of Life

One of the defining characteristics of Ancient Greek philosophy was its practical orientation. For Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, the Epicureans, and the Cynics, philosophy was fundamentally a way of life. To philosophize meant to engage in practices that transformed the soul, disciplined desires, clarified judgment, and aligned one’s life with truth.

Socrates exemplifies this orientation. He did not write treatises or construct formal systems. Instead he engaged others in dialogue, questioning their assumptions about virtue, justice, piety, and knowledge. His philosophy consisted not in transmitting doctrines but in cultivating self examination. The famous claim that the unexamined life is not worth living expresses the ancient conviction that philosophy is inseparable from ethical existence.

Plato developed this insight into a comprehensive vision. In his dialogues, philosophical inquiry aims at turning the soul away from illusion toward reality. Education is understood as a process of conversion, not merely the acquisition of information. The philosopher is someone whose entire life is oriented toward the contemplation of truth and the good.

Aristotle, while more systematic and empirical, maintained the same fundamental view. For him, philosophy culminates in wisdom, which involves both theoretical understanding and practical excellence. Ethics is not an optional branch but a central component of philosophical life. Knowledge of virtue is meaningful only insofar as it shapes character and action.

Later schools preserved this ideal. Stoicism emphasized the cultivation of inner freedom through rational control of passions. Epicureanism sought tranquility through understanding nature and limiting desires. Even skepticism functioned as a therapeutic practice aimed at freeing the mind from dogmatic anxiety. In all cases philosophy addressed the whole person.

Institutional Context in Ancient Greece

The institutional forms of philosophy in Ancient Greece differed markedly from modern structures. Philosophical schools such as Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, and later Hellenistic schools were not universities in the modern sense. They were communities organized around shared ways of life, methods of inquiry, and ethical commitments.

Membership in these schools involved personal mentorship, dialogue, and long term formation. Teachers were not merely lecturers but moral exemplars. Students did not pursue philosophy as a career in the modern professional sense but as a mode of existence. While some philosophers earned income through teaching or patronage, philosophy was not primarily a profession governed by standardized credentials.

Moreover, philosophical discourse was closely connected to public life. Philosophers participated in political debates, advised rulers, educated citizens, and engaged with poets and legislators. Even when critical of existing political systems, as Plato often was, philosophy addressed itself to the question of how a just society ought to be ordered.

Attitude Toward Knowledge and Truth in Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece knowledge was understood as a transformative encounter with truth. Truth was not merely propositional correctness but a disclosure of reality that shaped the knower. To know was to see more clearly, and this clarity carried ethical implications.

This conception is evident in the Greek emphasis on contemplation. Theoria originally referred to a form of attentive seeing. Philosophical contemplation was valued because it aligned the soul with the rational order of the cosmos. The pursuit of truth was inseparable from reverence for that order.

Importantly, this attitude did not exclude critical debate or disagreement. Greek philosophy was highly argumentative and pluralistic. However, disagreement occurred within a shared conviction that truth matters for life and that rational inquiry can guide human flourishing.

Transition Toward Modern Philosophy

The transformation of philosophy did not occur suddenly but unfolded over centuries. The Roman period, Christian thought, medieval scholasticism, and early modern philosophy all contributed to reshaping the nature of philosophical activity.

In medieval Europe philosophy became integrated into theological frameworks. While still oriented toward wisdom, it increasingly functioned as a supporting discipline for theology. Scholasticism emphasized systematic argumentation, logical rigor, and textual commentary. Philosophy remained connected to ethics and metaphysics but operated within institutional structures such as universities that introduced new forms of specialization.

The early modern period marked a decisive shift. Thinkers such as Descartes, Bacon, and later Kant redefined philosophy in response to scientific developments and epistemological concerns. The focus moved toward questions of method, certainty, and the limits of knowledge. Philosophy increasingly defined itself in relation to science rather than as a comprehensive way of life.

Philosophy in the Modern Western World

In the modern Western world philosophy is primarily an academic discipline. It is studied, taught, and practiced within universities, governed by professional norms, publication standards, and specialized subfields. This institutionalization has brought both gains and losses.

On the one hand, modern philosophy benefits from methodological precision, historical scholarship, and engagement with other disciplines. The professionalization of philosophy has enabled detailed analysis of logic, language, ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics. Philosophers contribute to debates in science, law, politics, and technology.

On the other hand, philosophy has largely lost its role as a way of life. For most practitioners and students, philosophy is not a comprehensive ethical practice but an intellectual activity pursued within limited contexts. The personal transformation of the philosopher is rarely considered a criterion of philosophical success.

Specialization and Fragmentation

One of the most striking differences between Ancient Greek and modern Western philosophy is the degree of specialization. Modern philosophy is divided into numerous subdisciplines, each with its own methods, terminology, and literature. Scholars often focus on narrow problems within epistemology, philosophy of language, ethics, or philosophy of mind.

This fragmentation contrasts sharply with the ancient ideal of philosophical unity. Greek philosophers did not sharply separate metaphysics, ethics, politics, and natural philosophy. Modern specialization has increased analytical rigor but at the cost of integrative vision.

As a result, contemporary philosophy often struggles to address questions of meaning, purpose, and the good life in a comprehensive way. Such questions are sometimes relegated to psychology, literature, or religion, whereas in antiquity they were central philosophical concerns.

Attitude Toward Practice and Application

In Ancient Greece philosophy was expected to guide life. The practical consequences of philosophical beliefs were openly acknowledged and debated. A philosopher’s credibility depended in part on the coherence between thought and conduct.

In the modern Western world philosophy is frequently regarded as abstract and impractical. While applied ethics, political philosophy, and philosophy of technology address real world issues, the dominant image of philosophy remains theoretical. Many philosophers do not claim that their work should directly influence how individuals live.

This shift reflects broader cultural changes. Modern societies often prioritize technological efficiency, economic productivity, and empirical science. Philosophy competes with these domains and often adopts their models of expertise and neutrality. As a result, philosophical inquiry tends to avoid normative claims about how one ought to live, focusing instead on analysis and critique.

Relationship Between Philosophy and Education

In Ancient Greece philosophical education aimed at forming character and judgment. The goal was not merely to transmit knowledge but to cultivate wisdom. Learning occurred through dialogue, memorization of texts, ethical exercises, and participation in communal life.

Modern philosophical education emphasizes critical thinking, argumentative skills, and familiarity with historical and contemporary debates. While these skills are valuable, they are often detached from ethical formation. Students may study moral philosophy without any expectation that it will shape their personal conduct.

Furthermore, philosophy is no longer central to general education. In antiquity philosophy was considered essential for free citizens. In modern curricula it is often optional or marginal, especially outside the humanities.

Philosophy and Public Life

Ancient Greek philosophy was deeply engaged with public life. Philosophers addressed questions of justice, law, education, and political organization. Even when critical of democracy or existing institutions, they assumed that philosophy had a public responsibility.

In contrast, modern philosophy often occupies a marginal position in public discourse. While some philosophers engage with social and political issues, philosophical voices are frequently overshadowed by economists, scientists, and media commentators. Philosophy’s influence on public policy and cultural values is indirect and limited.

This marginalization is partly self imposed. Professional philosophy often values technical sophistication over accessibility. Ancient philosophers wrote in ways that addressed educated citizens, whereas modern philosophical writing is often directed primarily at specialists.

Conceptions of the Philosopher

The figure of the philosopher differs profoundly between the two periods. In Ancient Greece the philosopher was a seeker of wisdom whose life embodied philosophical commitments. The philosopher was expected to display moderation, courage, and integrity.

In the modern Western world the philosopher is typically a scholar, researcher, or teacher. Professional competence is measured by publications, citations, and institutional recognition rather than by ethical example. This does not imply moral deficiency, but it reflects a different understanding of the philosopher’s role.

The ancient model emphasized personal transformation. The modern model emphasizes intellectual contribution. These models are not mutually exclusive, but modern institutions strongly favor the latter.

Attitude Toward Tradition and Authority

Ancient Greek philosophers engaged critically with tradition but also viewed themselves as participants in a shared cultural conversation. Myth, poetry, and religious practices were not simply rejected but reinterpreted.

Modern philosophy often defines itself through rupture. The early modern period emphasized breaking with tradition to establish secure foundations. This attitude persists in contemporary thought, where innovation is often valued over continuity.

As a result, philosophy can become disconnected from historical wisdom traditions. While historical scholarship exists, it is often treated as a separate subfield rather than as a living resource for philosophical practice.

Gains and Losses of Modern Philosophy

The transformation from ancient to modern philosophy brought undeniable gains. Analytical clarity, scientific integration, and methodological rigor expanded the scope of philosophical inquiry. Modern philosophy has contributed to logic, cognitive science, political theory, and ethics in ways unimaginable in antiquity.

At the same time, something essential was lost. Philosophy ceased to function as a comprehensive art of living for most people. Its capacity to address existential questions in a holistic way diminished. The ancient concern with wisdom, understood as the integration of knowledge and virtue, was replaced by a narrower conception of intellectual achievement.

Contemporary Attempts at Recovery

In recent decades some philosophers have sought to recover aspects of the ancient conception. Movements such as virtue ethics, existential philosophy, philosophical counseling, and renewed interest in Stoicism reflect dissatisfaction with purely academic approaches.

Scholars have also reexamined ancient philosophy as a practical discipline. Studies emphasize spiritual exercises, ethical practices, and the role of philosophy in shaping life. These developments suggest a growing recognition that philosophy’s original orientation still has relevance.

However, these efforts operate within modern institutional constraints. They represent adaptations rather than a full return to the ancient model.

Conclusion

The differences between philosophy in Ancient Greece and the modern Western world reflect profound changes in cultural values, institutions, and conceptions of knowledge. Ancient Greek philosophy functioned as a way of life oriented toward wisdom, ethical transformation, and understanding the order of reality. Modern Western philosophy functions primarily as an academic discipline focused on analysis, critique, and specialized research.

Both approaches have strengths. The ancient model offers depth, integration, and existential relevance. The modern model offers precision, breadth, and interdisciplinary engagement. The challenge for contemporary philosophy is to balance these dimensions.

Understanding the ancient conception of philosophy does not require abandoning modern achievements. Rather, it invites reflection on the purpose of philosophical inquiry and its role in human life. By reconsidering philosophy not only as a body of knowledge but as a practice oriented toward wisdom, the modern world may recover a dimension of thought that once stood at the heart of philosophical tradition.