Philosophy has long sought to clarify the most fundamental questions that arise from human reflection. Across different cultures and historical periods, thinkers have attempted to understand reality, knowledge, values, and social life through systematic reasoning. Although philosophical inquiry is vast and diverse, its central concerns tend to recur in recognizable forms. These recurring lines of inquiry provide a structured way to approach philosophy as a unified yet multifaceted discipline.

Overview

Philosophy is often described as the disciplined attempt to understand the most general features of reality, knowledge, and human life through reasoned reflection. Despite its diversity, the field has developed recognizable areas of inquiry that organize questions and methods in a coherent way. It helps clarify how these areas relate to one another and why they continue to matter.

From antiquity to the present, philosophers have disagreed not only about answers but also about what counts as a legitimate question. Some have focused on the structure of reality itself, others on the conditions of knowledge, others on how humans ought to live.

Understanding these branches is not merely an academic exercise. Each branch addresses fundamental aspects of human experience and provides conceptual tools that influence science, politics, religion, and culture. Examining the main branches of philosophy allows one to see philosophy as an interconnected tradition rather than a collection of isolated doctrines.

What Are the Branches of Philosophy

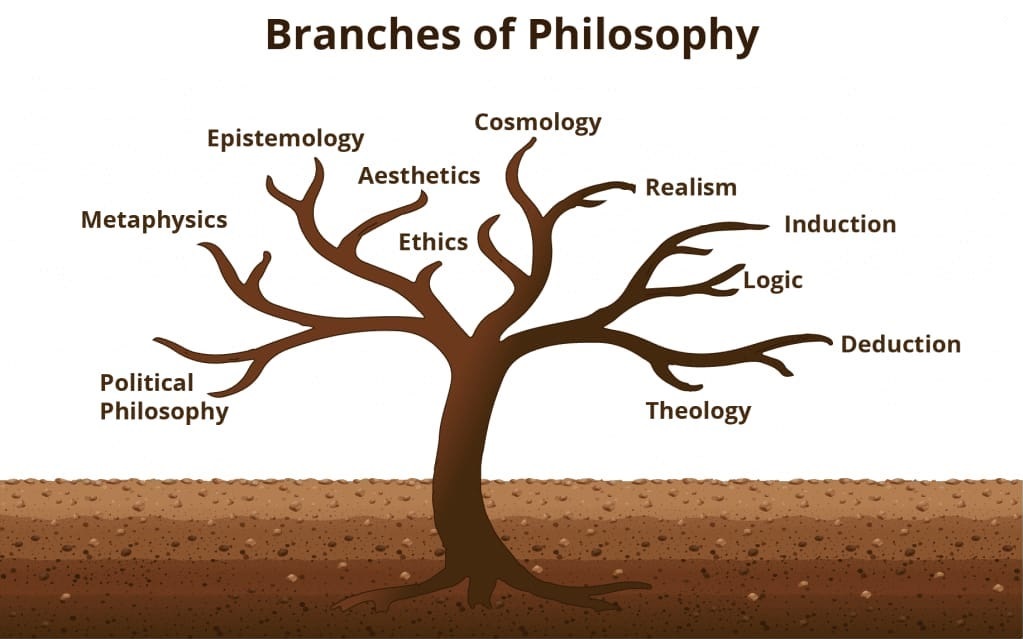

When asking the question, one is really asking how philosophical problems have been grouped historically. The most common division identifies metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, logic, and aesthetics as the core areas. Some classifications also include political philosophy, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language as distinct fields.

These divisions are not rigid. Many philosophers work across multiple areas, and major works often address several branches at once. Plato’s dialogues combine metaphysical speculation with ethical inquiry and political theory. Kant’s critical philosophy reshaped epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics simultaneously.

Nevertheless, the traditional division remains useful. It provides a conceptual map that helps students and readers navigate complex discussions. A clear sense of the main branches of philosophy associated with each area makes it easier to understand both historical development and contemporary debate.

Metaphysics and the Question of Reality

Metaphysics is concerned with the most general questions about what exists and how reality is structured. It asks about being, substance, causality, time, and identity. Metaphysics is often considered the most abstract, yet it underlies many other inquiries.

Aristotle is commonly regarded as a foundational figure in metaphysics. His analysis of being as being and his account of substance shaped philosophical vocabulary for centuries. Plato, through his theory of forms, proposed a reality beyond the changing world of experience. In the modern period, thinkers such as Descartes and Leibniz developed metaphysical systems grounded in reason and mathematical clarity.

In contemporary philosophy, metaphysics continues to evolve. Debates over realism, materialism, and the nature of causation show that questions about reality remain unresolved. Within any discussion of the main branches of philosophy, metaphysics occupies a central place because it frames how other philosophical questions are understood.

Epistemology and the Nature of Knowledge

Epistemology examines knowledge, belief, and justification. It asks how humans know what they claim to know and what distinguishes knowledge from mere opinion. This branch gained particular prominence in the early modern period, when scientific advances forced philosophers to reconsider the sources and limits of certainty.

Plato already raised epistemological questions by distinguishing knowledge from belief and linking true knowledge to unchanging forms. In the modern era, Rene Descartes sought indubitable foundations through methodical doubt, while John Locke emphasized experience as the source of ideas. David Hume pushed empiricism to skeptical conclusions, questioning causality and the self.

Immanuel Kant attempted to resolve these tensions by arguing that knowledge arises from the interaction between sensory input and conceptual structures of the mind. Epistemology remains a core component, because it directly affects how philosophical arguments are evaluated and how truth claims are justified.

Ethics and the Problem of the Good Life

Ethics addresses questions of value, obligation, and the good life. It asks how humans ought to act and what makes actions right or wrong. Among the major branches of philosophy, ethics is often the most immediately practical, as it directly informs personal and social decision making.

Aristotle’s virtue ethics emphasized character and the cultivation of excellence through habit. For him, ethical life aims at flourishing within a community. In contrast, Immanuel Kant grounded morality in rational duty and universal principles, arguing that moral law arises from reason itself. Utilitarian thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill evaluated actions by their consequences, especially the promotion of overall well being.

Modern ethical theory continues to develop these approaches while addressing new challenges. Bioethics, environmental ethics, and applied ethics demonstrate how classical ideas are adapted to contemporary contexts. Any account of the main branches of philosophy must include ethics because it connects abstract reflection with lived experience.

Logic as the Study of Reasoning

Logic investigates the principles of valid reasoning and argumentation. It asks how conclusions follow from premises and how fallacies can be identified. Although sometimes treated as a technical discipline, logic has been integral to philosophy since its beginnings.

Aristotle’s syllogistic logic provided the first systematic account of deductive reasoning. In the modern period, thinkers such as Gottlob Frege transformed logic through formal systems that influenced mathematics and computer science. Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein further explored the relationship between logic, language, and reality.

Logic supports all other branches by providing standards of clarity and consistency. Without logical analysis, philosophical discussion risks becoming vague or incoherent. For this reason, logic occupies a unique position within the branches of philosophy.

Aesthetics and the Experience of Beauty

Aesthetics explores questions of beauty, art, and aesthetic judgment. It asks what makes something beautiful, how artistic meaning is created, and whether aesthetic values are subjective or objective. Although sometimes considered less central, aesthetics addresses fundamental aspects of human experience.

Plato was suspicious of art, viewing it as imitation removed from truth. Aristotle offered a more positive account, emphasizing the educational and emotional value of tragedy. In the modern era, philosophers such as Kant analyzed aesthetic judgment as a unique form of reflective pleasure that is neither purely subjective nor strictly conceptual.

Contemporary aesthetics engages with new art forms and cultural contexts, examining issues of interpretation and value. Within a branches of philosophy, aesthetics illustrates how philosophy extends beyond abstract theory into culture and creativity.

Main Branches of Philosophy

It’s clear that no single thinker can be confined to one area. Plato contributed to metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and political philosophy. Aristotle’s work spans logic, metaphysics, ethics, and natural philosophy.

In the modern period, Kant reshaped multiple branches through his critical project. His influence extends across epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. In the twentieth century, figures such as Wittgenstein and Heidegger challenged traditional divisions by rethinking language and being in ways that cut across established categories.

This interconnectedness shows that they are best understood as perspectives rather than isolated compartments. Studying them together provides a more accurate picture of philosophical inquiry.

Political Philosophy and Social Order

Political philosophy examines power, authority, justice, and the organization of society. While sometimes treated as part of ethics, it has developed into a distinct field due to its focus on institutions and collective life.

Plato’s Republic offered an idealized vision of a just society governed by philosopher rulers. Aristotle analyzed constitutions and emphasized the role of civic virtue. In the modern era, thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean Jacques Rousseau developed theories of social contract that continue to influence political thought.

Contemporary political philosophy addresses issues of rights, equality, and global justice. Its inclusion among the main branches of philosophy highlights philosophy’s engagement with real world structures and conflicts.

Philosophy of Mind and Human Consciousness

Philosophy of mind investigates the nature of consciousness, thought, and personal identity. It asks how mental phenomena relate to the physical world and whether the mind can be reduced to brain processes.

Descartes’ dualism framed the modern problem by distinguishing mind from body. Later thinkers challenged this separation, proposing materialist or functional accounts of mind. In the twentieth century, philosophers such as Gilbert Ryle and Daniel Dennett criticized the idea of a separate mental substance.

Current debates about artificial intelligence and consciousness show that philosophy of mind remains a dynamic field. Within the major branches of philosophy, it connects metaphysical questions with scientific research.

Philosophy of Language and Meaning

Philosophy of language focuses on meaning, reference, and communication. It examines how language relates to thought and reality. This branch gained prominence in the twentieth century, particularly within analytic philosophy.

Frege’s distinction between sense and reference laid the groundwork for modern semantics. Wittgenstein’s later work emphasized language use within forms of life rather than abstract structures. These ideas reshaped philosophical method and influenced other branches.

Unity and Diversity in Philosophy

Despite its many branches, philosophy retains a sense of unity. The same fundamental questions reappear in different forms, and insights from one area often inform another. Metaphysical assumptions influence ethical theories, epistemological views shape political arguments, and logical analysis underpins all reasoning.

The study of the main branches of philosophy reveals this dynamic interaction. Rather than fragmenting thought, the division into branches provides multiple angles from which to approach enduring problems.

This unity within diversity explains why philosophy continues to develop without reaching final answers. Each generation revisits old questions with new tools and perspectives.

Conclusion

A systematic examination offer more than historical knowledge. It provides a framework for understanding how humans have sought to make sense of reality, knowledge, value, and meaning.

Philosophy is neither a closed system nor a random collection of ideas. It is an evolving conversation shaped by enduring problems and influential thinkers. By studying these branches together, one gains a deeper appreciation of philosophy’s role in shaping intellectual life.

Ultimately, the value of philosophy lies not in definitive answers but in disciplined questioning. The main purpose is to continue to guide this questioning, ensuring that reflection remains both rigorous and relevant.