Arthur Schopenhauer remains one of the most distinctive figures in nineteenth century philosophy. In an age dominated by German Idealism and the ambitious system building of thinkers such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Schopenhauer developed a radically different vision. Where others saw rational progress unfolding through history, he perceived blind striving. Where others celebrated reason as the core of reality, he posited an irrational force beneath all phenomena. Where many philosophers described the world as fundamentally intelligible and purposive, he described it as a theater of suffering.

His major work, The World as Will and Representation, articulates a metaphysical system that blends Kantian epistemology, Platonic forms, and insights drawn from Indian thought. The result is a philosophy that is austere, psychologically penetrating, and often unsettling. Yet Schopenhauer’s influence has been immense, shaping figures such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Richard Wagner, Sigmund Freud, and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

This article examines Schopenhauer’s life, his metaphysics of will, his theory of suffering, his ethics of compassion, his aesthetics, and his enduring relevance.

Life and Intellectual Context

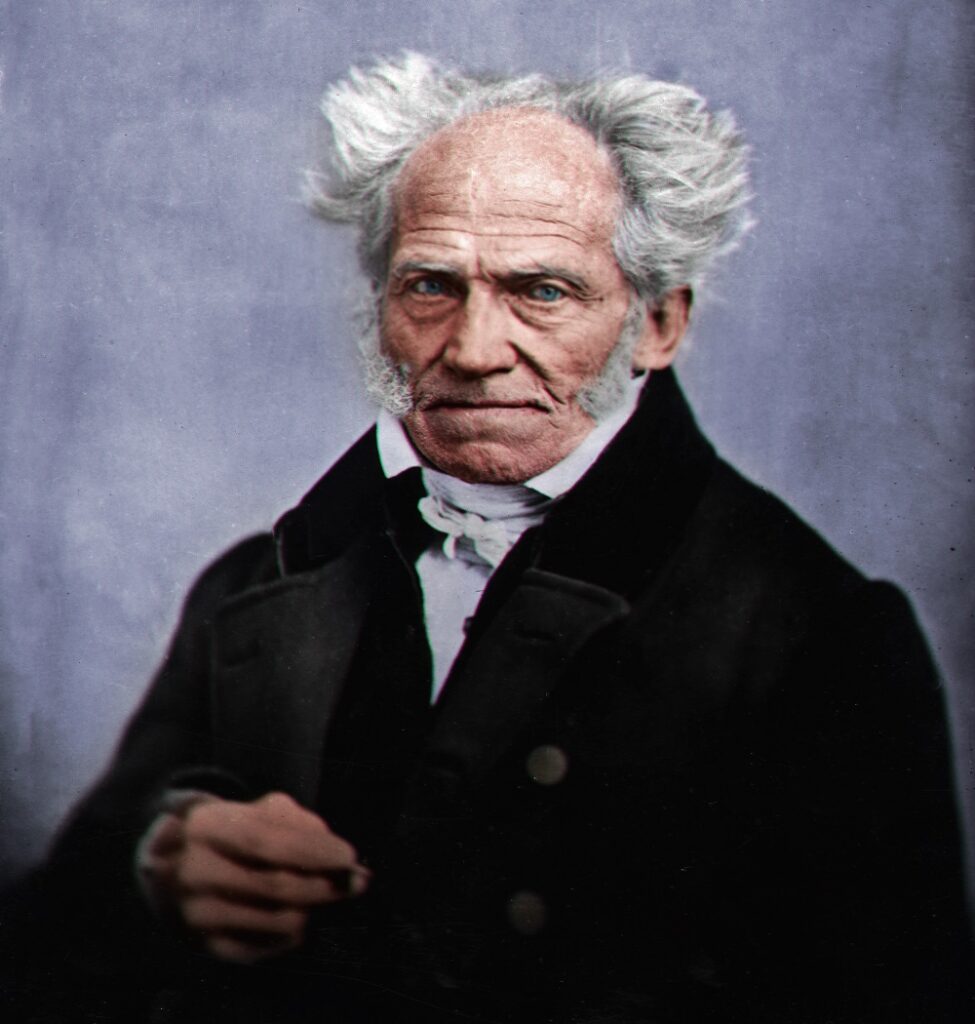

Schopenhauer was born in 1788 in Danzig, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia. His father was a wealthy merchant who intended his son for a commercial career. After his father’s death, Schopenhauer turned toward academic life. He studied in Göttingen and Berlin, engaging deeply with the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and later reacting strongly against the dominant post Kantian systems.

Berlin at the time was the intellectual center of German philosophy. Hegel’s lectures attracted large audiences. Schopenhauer, confident in his own originality, scheduled his lectures at the same hour as Hegel’s, hoping to compete. The result was a failure. Students chose Hegel. Schopenhauer’s lectures were poorly attended, and he eventually abandoned his academic career.

For much of his life, he remained marginal to the philosophical mainstream. Only later, especially after the publication of his essays and aphorisms, did he gain recognition. His personality was famously sharp, often caustic. He valued independence and cultivated the image of a solitary thinker. This solitude aligned with his philosophical vision: truth does not emerge from collective historical processes but from individual insight.

The World as Representation

Schopenhauer begins his major work with a Kantian premise: the world we experience is representation. Everything we perceive is structured by the forms of our cognition. Space, time, and causality are not properties of things in themselves but conditions of experience.

In this respect, Schopenhauer accepts Kant’s distinction between phenomena and the thing in itself. However, he departs from Kant in a decisive way. Kant maintained that the thing in itself is unknowable. Schopenhauer argues that we have one privileged access point to it: our own inner experience.

When I observe my body from the outside, it appears as an object among objects. But when I experience it from within, I encounter something different. I do not merely see movements; I feel striving, impulse, desire. This immediate awareness, Schopenhauer claims, reveals the inner essence of reality.

The world as representation is the surface. Beneath it lies the world as will.

The Metaphysics of Will

For Schopenhauer, the thing in itself is will. This does not mean conscious intention. The will is not rational planning. It is blind striving. It is a fundamental, aimless force that manifests in all natural phenomena.

The will expresses itself in gravity, magnetism, plant growth, animal instinct, and human desire. In humans, it appears as countless wants and drives. Yet these are not separate wills. They are expressions of a single, universal will.

This claim transforms metaphysics. Instead of a rational structure underlying reality, Schopenhauer posits an irrational dynamic. The world is not guided by reason or moral purpose. It is driven by ceaseless striving.

This striving has no final goal. Satisfaction of one desire leads only to the emergence of another. Life oscillates between desire and boredom. When we lack something, we suffer. When we obtain it, the absence of striving produces emptiness, which generates new desire. Thus existence is characterized by structural dissatisfaction.

Schopenhauer’s metaphysics is often described as pessimistic. Yet it is more precise to say that he sees suffering as intrinsic to the nature of will. As long as there is striving, there is lack. As long as there is lack, there is pain.

Individuality and Illusion

If there is only one will, why do we experience ourselves as separate individuals? Schopenhauer answers by appealing to the principium individuationis, the principle of individuation. Space and time divide the unified will into distinct appearances.

Individuality belongs to the world as representation. It is a mode of appearance. At the deeper level, all beings are expressions of the same underlying force. This insight has ethical consequences. If the apparent separation between self and other is superficial, then compassion is grounded in metaphysical unity.

In ordinary consciousness, however, the individual is dominated by egoism. Each organism strives for its own survival and advantage. Conflict is inevitable. Nature becomes a battlefield in which the will turns against itself through its own manifestations.

Suffering and Pessimism

Schopenhauer’s analysis of suffering is uncompromising. He surveys human life and finds it pervaded by anxiety, frustration, competition, and eventual death. Pleasure is fleeting and negative. It is the temporary cessation of pain. Pain, by contrast, is positive and immediate.

This asymmetry underlies his pessimism. He does not argue that life contains no joy. Rather, he argues that the structure of existence ensures that suffering predominates. Even apparent goods such as love and ambition are expressions of the will’s restless striving.

In love, individuals believe they pursue personal happiness. Yet Schopenhauer interprets sexual desire as the strategy of the species. The will uses individuals as instruments for reproduction. Personal longing masks a deeper biological compulsion.

Death does not provide consolation. The individual perishes, but the will persists in new forms. The cycle continues.

Aesthetics and the Suspension of Will

Despite this bleak diagnosis, Schopenhauer offers moments of release. Aesthetic experience allows temporary escape from the tyranny of will. In art, we contemplate objects without desire. We perceive them purely, free from practical concerns.

Music occupies a special place in his system. Unlike other arts, which represent particular objects, music expresses the will directly. It mirrors the inner structure of striving and resolution. For this reason, Schopenhauer regarded music as the highest art form.

This aesthetic theory profoundly influenced Wagner. It also shaped later reflections on art as a mode of transcendence. In aesthetic contemplation, the individual becomes a pure subject of knowledge. For a moment, striving ceases. The world is experienced without the pressure of desire.

Yet this state is temporary. After the artwork ends, the will reasserts itself.

Ethics of Compassion

Schopenhauer’s ethics emerges from his metaphysics. If all beings are manifestations of one will, then the suffering of another is not fundamentally alien. Compassion arises when the boundary between self and other weakens.

He rejects ethical systems based on rational duty or social contract. Moral action does not originate in abstract principles but in immediate sympathy. When one person perceives the suffering of another as his own, egoism is overcome.

Compassion leads to justice and benevolence. Justice refrains from harming others. Benevolence actively seeks their well being. Both rest on the recognition of shared essence.

This ethical vision has affinities with Buddhist and Hindu traditions, which Schopenhauer admired. He saw in them a profound understanding of suffering and the path toward renunciation.

Asceticism and Denial of the Will

The highest ethical stance, for Schopenhauer, is asceticism. The saint recognizes the futility of striving and turns away from desire. Through self denial, chastity, and detachment, the will is quieted.

This does not mean suicide. Suicide, in his view, is still an affirmation of the will. It expresses dissatisfaction with particular circumstances, not rejection of striving itself. True denial of the will involves inner transformation. Desire fades. The individual becomes indifferent to personal advantage.

Schopenhauer describes this state in terms that approach mysticism. The will turns against itself. The world as representation loses its grip. What remains is a quietude beyond ordinary categories.

Critique of Optimism and Progress

Schopenhauer was a fierce critic of philosophical optimism. He opposed the view that history unfolds rationally or that humanity advances toward moral perfection. He rejected the notion that suffering is justified by a greater good.

His critique extends to political and social theories that promise collective salvation. For him, suffering is rooted in the structure of existence, not in defective institutions alone. Reform may alleviate specific injustices, but it cannot abolish the restless nature of will.

This stance placed him at odds with many contemporaries. Yet it also insulated his philosophy from naive expectations. He does not promise redemption through progress. He offers insight into the human condition as such.

Influence on Later Thought

Schopenhauer’s impact has been wide ranging. Nietzsche initially embraced him as an educator who revealed the tragic dimension of life. Although Nietzsche later rejected Schopenhauer’s ascetic conclusion, the early influence is evident.

Freud’s theory of unconscious drives echoes the concept of blind will. While Freud developed a clinical and scientific framework, the idea that human behavior is shaped by forces beneath rational awareness resonates with Schopenhauer’s insights.

Wittgenstein’s reflections on the limits of language and the ethical dimension beyond factual description also show traces of Schopenhauer’s distinction between the world as representation and what lies beyond.

In literature, authors such as Thomas Mann and Samuel Beckett engaged deeply with his themes of futility and desire. In music and art theory, his elevation of aesthetic experience as metaphysical revelation left a lasting mark.

Relevance Today

In contemporary culture, characterized by consumerism and constant stimulation, Schopenhauer’s analysis of desire remains striking. The cycle of wanting, acquiring, and wanting again is visible in modern economic life. His claim that satisfaction does not eliminate striving but merely redirects it appears psychologically astute.

At the same time, his ethics of compassion addresses global interdependence. If individuality is ultimately superficial, then narrow egoism is philosophically indefensible. Compassion becomes not sentimental indulgence but recognition of shared essence.

His critique of progress also resonates in an era of technological acceleration. Advances in science and industry have transformed living conditions, yet they have not abolished anxiety, competition, or existential dissatisfaction. Schopenhauer’s framework suggests that these are not accidental features of society but expressions of deeper dynamics.

Objections and Criticisms

Schopenhauer’s system has faced many objections. Critics question whether the inference from inner experience to universal will is justified. Even if we experience our own striving directly, does it follow that all reality is will?

Others argue that his pessimism exaggerates suffering and neglects genuine fulfillment. Human relationships, creativity, and moral achievement may involve more than the temporary suspension of pain.

There is also tension between his metaphysics and modern science. The concept of will as the essence of matter does not align easily with contemporary physics. Some interpret his theory metaphorically rather than literally.

Yet even where his metaphysical claims are contested, his psychological observations retain force. The description of desire, competition, and frustration speaks to enduring aspects of human life.

Conclusion

Arthur Schopenhauer constructed a philosophy that challenges comforting narratives. He portrays the world as representation structured by our cognition and as will characterized by blind striving. From this metaphysics he derives a sober account of suffering, an ethics grounded in compassion, and a path of aesthetic and ascetic release.

His thought refuses easy consolation. It does not promise historical redemption or rational harmony. Instead, it invites reflection on the restless nature of existence and the possibility of inner transformation.

More than a system builder, Schopenhauer was a diagnostician of the human condition. His influence on philosophy, psychology, literature, and art testifies to the depth of his insight. Whether one accepts his metaphysics in full or not, engagement with his work sharpens awareness of desire, suffering, and the fragile moments of peace that punctuate them.

In this sense, Schopenhauer remains not merely a figure of the nineteenth century but a thinker whose questions continue to press upon the present.