The claim that medieval science and philosophy associated with the Islamic world were not genuinely Islamic in origin can be formulated in a historically focused way by shifting attention from peoples and identities to civilizations and institutions. When framed at this level, the argument concerns the sources of knowledge, the structures that sustained or limited inquiry, and the role of political power and language in shaping intellectual life. It does not require judgments about innate capacities. It asks instead whether Islamic civilization, as an institutional and normative order, generated an autonomous philosophical and scientific tradition, or whether it primarily functioned as a vehicle for the preservation and administration of earlier intellectual inheritances.

Pre-Islamic Civilizations as Primary Sources of Knowledge

By the time Islam emerged in the seventh century, the major foundations of philosophy and science were already firmly established elsewhere. Greek philosophy had developed comprehensive systems of logic, metaphysics, ethics, and natural philosophy. Roman civilization had absorbed and transmitted much of this knowledge through law, engineering, and administration. Persian traditions contributed statecraft, astronomy, and medical learning. Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures had long traditions of mathematics, medicine, and observational science. Jewish scholarship preserved and interpreted philosophical and theological ideas across centuries.

None of these traditions originated within Islamic civilization. They were pre-Islamic, geographically widespread, and intellectually mature long before Arab conquests. When Islamic polities expanded rapidly across the Near East, North Africa, and parts of Europe, they incorporated regions that already possessed libraries, schools, and scholarly languages such as Greek, Syriac, Persian, and Latin.

From a civilizational perspective, this means that the raw intellectual material encountered by Islamic rulers was external and inherited rather than internally generated.

Conquest, Administration, and the Role of Language

The early Islamic empires were mainly political and military formations. Their primary institutional concerns were governance, taxation, law, and religious regulation. As conquered territories were integrated, Arabic gradually became the administrative and scholarly language. This process, often described as Arabization, did not create new knowledge by itself. It translated existing bodies of knowledge into a new linguistic medium.

The adoption of Arabic as a scholarly language can be compared to the role of Latin in medieval Europe. Latin functioned as an administrative and intellectual lingua franca without implying that all Latin writers were ethnically Roman or that Roman civilization was the sole origin of medieval thought. Similarly, Arabic became a unifying language for diverse populations, including Persians, Syriac Christians, Jews, and others.

From an institutional standpoint, the use of Arabic indicates political unification rather than intellectual origination.

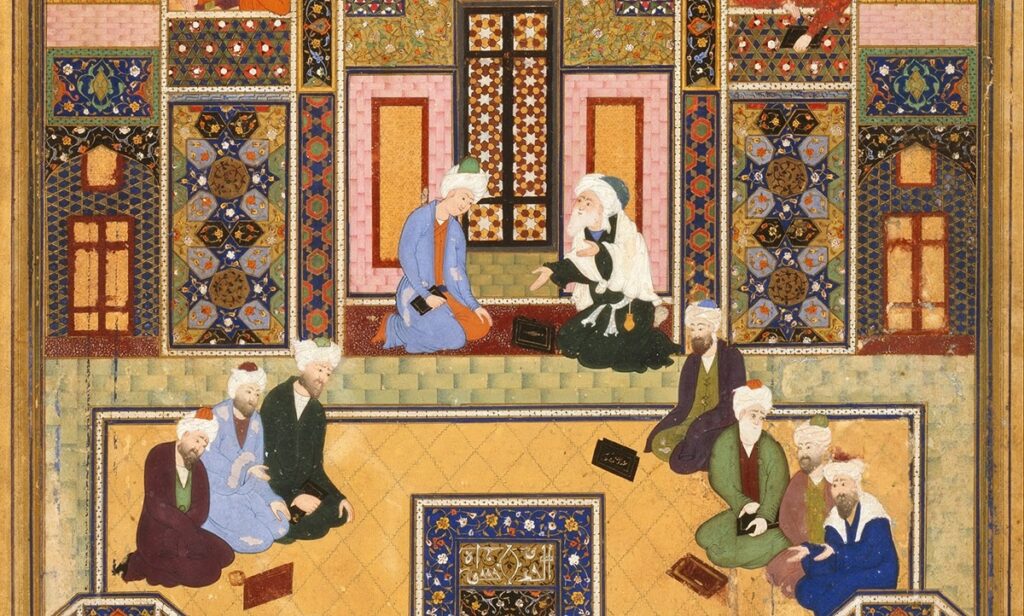

The Translation Movement as Civilizational Mediation

The large-scale translation efforts of the Abbasid period are often cited as evidence of Islamic intellectual vitality. However, these efforts can be interpreted differently when examined institutionally. Translation is not creation. It is mediation.

Texts by Aristotle, Galen, Euclid, Ptolemy, and other Greek authorities were rendered into Arabic largely by scholars trained in earlier traditions. The institutional motive behind this activity was pragmatic. Medicine was needed for courts and armies. Astronomy was needed for calendars and navigation. Logic was useful for theology and law.

The translation movement reflects selective appropriation rather than an internally driven philosophical project. The choice of texts was instrumental, oriented toward utility within existing religious and political frameworks, not toward the open-ended pursuit of speculative inquiry.

Philosophy Under Religious and Legal Constraints

A key question for any civilization claiming philosophical autonomy is whether philosophy is treated as an independent mode of inquiry or subordinated to external norms. In Islamic civilization, philosophy was consistently constrained by religious law and theology. Philosophical inquiry was tolerated insofar as it did not challenge core doctrinal commitments.

Institutions of higher learning were primarily religious. Their central disciplines were jurisprudence, Quranic exegesis, and theology. Philosophy had no secure institutional autonomy comparable to the academies of classical Greece or the later universities of Europe. It existed at the margins, dependent on patronage, and vulnerable to theological opposition.

From a civilizational standpoint, this indicates that philosophy was never fully integrated as a legitimate and self-governing discipline.

Science as Applied Knowledge Rather Than Theoretical Autonomy

Scientific activity in the medieval Islamic world was largely applied rather than theoretical. Medicine served courts. Astronomy served calendrical and religious needs. Mathematics served inheritance law and administration. These activities required technical competence but did not necessarily foster foundational questioning.

The absence of institutional separation between science and theology limited the development of critical scientific method. Where science exists primarily to support legal or religious functions, its scope remains constrained. Theoretical challenges to inherited models risked theological consequences.

This institutional structure differs fundamentally from civilizations in which scientific inquiry gradually achieved independence from religious authority.

The Question of Decline and Institutional Fragility

The later decline of scientific and philosophical activity within Islamic civilization can be understood as evidence of institutional fragility rather than accidental loss. Traditions that depend on patronage and lack institutional autonomy are vulnerable to political and theological shifts.

When patronage ended or theological priorities hardened, philosophy and science had no stable institutional base from which to resist suppression. This suggests that these disciplines were never structurally central to the civilization itself.

By contrast, in Europe, philosophy and science eventually became embedded within universities and secular institutions capable of sustaining inquiry across political changes.

Contemporary Implications Without Cultural Essentialism

Observing the relative weakness of philosophy and science in many contemporary Islamic societies does not require claims about culture or ethnicity. It points instead to long-term institutional patterns. Civilizations that do not develop autonomous structures for critical inquiry struggle to regenerate them once they collapse.

The issue is not who people are, but how inquiry is organized, protected, and valued within a civilization.

Conclusion

When examined at the level of civilizations and institutions, the claim that medieval Islamic civilization did not generate an autonomous philosophical or scientific tradition becomes a historically arguable position. Pre-Islamic civilizations supplied the foundational knowledge. Islamic empires provided political unification and linguistic mediation. Philosophy and science were tolerated instrumentally but never institutionalized as independent disciplines.

This interpretation does not deny the presence of scholars or technical achievements. It argues instead that Islamic civilization functioned primarily as a conduit and administrator of inherited knowledge rather than as a source of fundamentally new philosophical or scientific paradigms. Understanding this distinction allows for critical historical analysis without resorting to essentialist explanations.