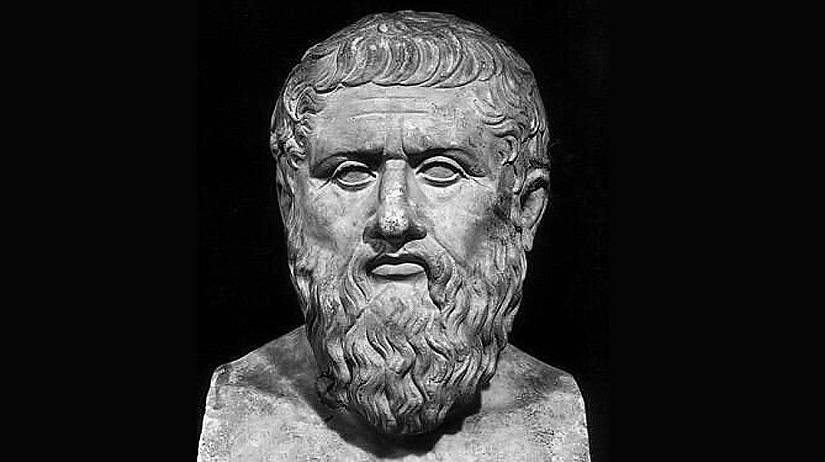

Plato stands at the origin of nearly every major question in Western philosophy. His thought shaped metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, psychology, and aesthetics in ways that still define how these subjects are discussed. More than two thousand years after his death, philosophers continue to debate problems in terms first articulated in his dialogues. Plato’s work does not belong only to the history of philosophy. It remains a living source of reflection about reality, knowledge, justice, education, and the human soul.

What makes Plato unique is not merely the range of topics he addresses but the unity with which he treats them. Questions about what exists, how we know, how we should live, and how societies should be organized are inseparable for him. Understanding reality is inseparable from understanding how a person ought to live. Knowledge and ethics are intertwined, and political life reflects the structure of the human soul.

This article presents a comprehensive account of Plato’s philosophy at full length. It explores the dialogical form of his writing, his theory of Forms, his account of knowledge and recollection, his conception of the soul, his ethics and political philosophy, his views on education, art, and love, and his influence on later thought.

The Dialogical Form and the Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

Plato did not write treatises. He wrote dialogues, conversations in which characters question, challenge, and refine one another’s views. Socrates often appears as the central figure, leading others through careful questioning that exposes contradictions and encourages deeper understanding.

This literary form is not accidental. Plato believed that philosophy is not a body of information to be transmitted but an activity of inquiry. Knowledge cannot be handed down as a set of conclusions. It must be discovered through reflection and argument. The dialogue invites readers to participate in the process rather than remain passive recipients.

The dialogical method also mirrors the philosophical process itself. Questions remain open, arguments develop gradually, and conclusions often emerge indirectly. Plato’s writing forces readers to think alongside the characters rather than simply observe them.

In many dialogues, apparent confusion or aporia, a state of puzzlement, is not a failure but a deliberate philosophical moment. Plato uses these moments to show that genuine understanding often begins with recognizing the limits of one’s assumptions. The reader is drawn into a shared experience of inquiry rather than offered a finished doctrine.

The dramatic setting of the dialogues also allows Plato to explore philosophical ideas through personalities, emotions, and social contexts. Philosophy appears not as an abstract exercise but as something embedded in human interaction, friendship, disagreement, and persuasion.

The Theory of Forms: The Heart of Plato’s Metaphysics

The most distinctive element of Plato’s philosophy is the theory of Forms. Plato argued that beyond the world of sensory experience lies a realm of unchanging, intelligible realities. These Forms are not physical objects but perfect standards of qualities such as justice, beauty, equality, and goodness.

Physical things are always changing, imperfect, and subject to decay. Yet we speak meaningfully about justice, beauty, or equality as if they possess stable meaning. Plato explains this by arguing that such concepts refer to real, non material Forms that provide standards by which we judge particular instances.

A just action is just because it participates in the Form of Justice. A beautiful object is beautiful because it reflects the Form of Beauty. The Forms are more real than physical objects because they are eternal and unchanging.

This metaphysical structure also explains why knowledge is possible. If everything were in constant flux, as some pre Socratic thinkers claimed, stable knowledge would be impossible. The existence of Forms provides an anchor for rational thought and allows understanding to reach beyond perception.

Plato’s Forms are not merely abstract ideas. They are presented as the true objects of intellectual vision, realities that the mind can grasp through disciplined reasoning and philosophical training.

Knowledge, Opinion, and Recollection

Plato distinguishes sharply between knowledge and opinion. Opinion concerns the changing world of appearances. Knowledge concerns the unchanging realm of Forms.

In dialogues such as the Meno and the Phaedo, Plato develops the theory of recollection. He suggests that the soul existed before birth and contemplated the Forms directly. Learning in this life is therefore a process of remembering what the soul already knows at a deeper level.

This view emphasizes that genuine knowledge arises from rational reflection rather than sensory experience. Perception provides examples, but understanding comes from intellectual insight.

The Allegory of the Cave and Intellectual Liberation

In the Republic, Plato presents the allegory of the cave to illustrate the human condition. Prisoners chained inside a cave see only shadows projected on a wall and mistake these shadows for reality. When one prisoner escapes and sees the world outside, he realizes how limited his previous understanding was.

The allegory represents the journey from ignorance to knowledge. Most people live among appearances without recognizing their limitations. Philosophical education frees the mind and allows it to grasp deeper truths.

The allegory also highlights the difficulty of enlightenment. Those who remain in the cave often resist those who attempt to show them a broader reality.

The Structure of the Soul

Plato’s ethical and psychological thought centers on his account of the soul. He divides the soul into three parts: rational, spirited, and appetitive.

The rational part seeks truth and understanding. The spirited part is associated with courage and emotion. The appetitive part desires bodily pleasures and material satisfaction. A well ordered life requires that reason govern the other parts.

This model explains internal conflict. When appetite or emotion overrides reason, disorder arises. Virtue consists in harmony among the parts of the soul under the guidance of reason.

Plato’s tripartite model is not meant as a biological description but as a philosophical framework for understanding motivation and moral struggle. It captures the complexity of human behavior and the need for internal discipline.

The structure of the soul also parallels the structure of the state in the Republic, reinforcing Plato’s belief that personal and political order reflect the same underlying principles.

Ethics and the Pursuit of the Good

For Plato, ethics is inseparable from knowledge. To know the good is to be drawn toward it. Wrongdoing results from ignorance rather than deliberate malice.

The highest aim of life is to align the soul with the Form of the Good, which Plato describes as the ultimate source of truth and value. The good life is characterized by inner harmony, wisdom, and justice.

Virtue is therefore not a matter of external success but of internal order and rational understanding.

Justice and the Ideal State

In the Republic, Plato examines justice by constructing an ideal city. The structure of the city mirrors the structure of the soul. Just as reason should govern the individual, wise rulers should govern the state.

Plato divides society into rulers, auxiliaries, and producers. Each class performs a function suited to its nature. Justice consists in each part doing its proper work without interfering with others.

This model emphasizes harmony, specialization, and the importance of wisdom in leadership.

Plato’s city is not merely a political blueprint but a philosophical analogy. By observing how justice functions in the city, readers gain insight into how justice should function within the individual soul.

The discussion of communal living among the guardian class, the regulation of education, and the careful selection of rulers illustrates Plato’s conviction that justice requires deliberate cultivation rather than spontaneous emergence.

Education as the Foundation of Society

Education is central to Plato’s philosophy. He believed that the character of individuals and the health of society depend on proper formation from an early age.

Education should cultivate reason, discipline emotion, and guide desire. Mathematics, music, and philosophy are essential tools for shaping the soul. The goal is moral and intellectual excellence rather than vocational skill.

Through education, individuals learn to turn away from appearances and toward truth.

Philosopher Kings and Political Authority

Plato famously argued that the best rulers are philosopher kings, individuals who understand the Forms and are therefore capable of governing wisely.

This proposal reflects Plato’s conviction that political authority must be grounded in knowledge and virtue. The purpose of the state is to create conditions in which citizens can live virtuous lives.

Although often criticized as impractical, this idea raises enduring questions about the relationship between knowledge, power, and justice.

Love, Beauty, and Ascent in the Symposium

In the Symposium, Plato explores the nature of love. Love begins with attraction to physical beauty but can ascend toward appreciation of beauty itself and finally toward contemplation of the Form of Beauty.

This ascent illustrates how desire can be redirected from the material to the intellectual. Love becomes a pathway to philosophical insight and spiritual development.

Beauty thus plays a crucial role in guiding the soul toward higher understanding.

Plato’s View of Art and Imitation

Plato’s treatment of art is complex. In the Republic, he criticizes poetry and drama for imitating appearances rather than truth. Art can mislead by appealing to emotion rather than reason.

At the same time, Plato recognizes the formative power of art. His concern is moral rather than aesthetic. Art should contribute to the cultivation of virtue and understanding.

This tension continues to influence debates about art and society.

Plato’s Cosmology in the Timaeus

In the Timaeus, Plato presents a cosmological account of the universe. He describes a divine craftsman who orders chaotic matter according to rational principles. The universe, in this account, is structured and intelligible.

Although mythic in form, this account reflects Plato’s conviction that reality is rationally ordered and accessible to understanding.

The Immortality of the Soul

Plato argues in several dialogues that the soul is immortal. The soul’s capacity for knowledge and its affinity with the Forms suggest that it is not merely a physical entity.

This belief reinforces the ethical dimension of his philosophy. If the soul endures beyond bodily life, the pursuit of wisdom and virtue gains deeper significance.

Plato’s Influence on Later Thought

Plato’s ideas shaped Neoplatonism, early Christian theology, medieval scholasticism, and Renaissance humanism. His questions and methods influenced the development of logic, metaphysics, and ethics for centuries.

Even modern philosophy bears the imprint of Platonic themes. Debates about universals, knowledge, and moral values often trace their roots to his work.

Neoplatonic thinkers expanded the theory of Forms into elaborate metaphysical systems. Christian philosophers adapted Platonic ideas to articulate doctrines of the soul and divine reality. Medieval scholars treated Plato as a foundational authority alongside Aristotle.

In the modern era, philosophers such as Descartes, Kant, and Hegel engaged deeply with Platonic problems, even when rejecting his conclusions. The persistence of these themes shows how deeply Plato’s questions shaped the intellectual landscape of

Criticisms and Reinterpretations

Plato has been criticized for positing a realm of Forms that seems metaphysically extravagant. Others question the feasibility of philosopher kings or his skepticism toward democracy and art.

These criticisms reflect the enduring vitality of his thought. Plato’s philosophy provokes engagement rather than fading into historical curiosity.

The Unity of Plato’s Vision

Despite addressing diverse topics, Plato’s philosophy is unified by the belief that reality is intelligible and that human beings can orient their lives toward truth and goodness.

Metaphysics, ethics, politics, and education are interconnected aspects of a single philosophical vision. Understanding reality and living well are parts of the same pursuit.

Why Plato Still Matters

Plato matters because he addresses questions that cannot be avoided. What is real. What can be known. What is justice. How should one live. These questions remain central regardless of historical change.

Engaging with Plato is not an antiquarian exercise but a living philosophical experience that challenges assumptions and invites reflection.

Conclusion

Plato’s philosophy represents one of the most comprehensive attempts to understand reality, knowledge, and human life as a coherent whole. Through the theory of Forms, the analysis of the soul, the examination of justice, and the emphasis on education, Plato presents philosophy as a guide to life.

His thought continues to shape intellectual history because it confronts fundamental questions with depth and seriousness. To read Plato is to enter a conversation that has never ceased, a conversation about truth, goodness, and the possibility of wisdom.