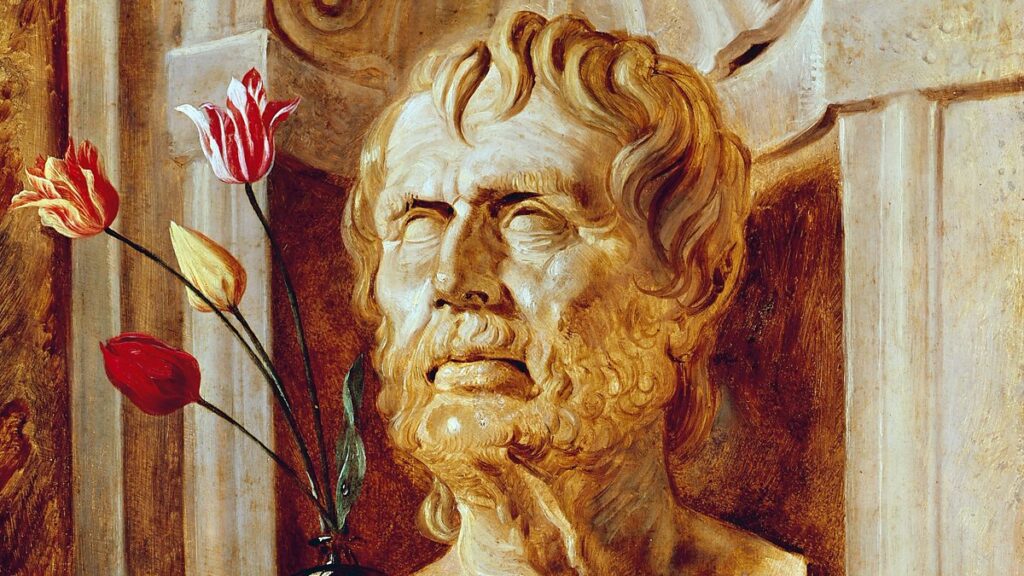

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, known simply as Seneca, was one of the most remarkable figures of ancient Rome. He was a statesman, dramatist, and philosopher who lived through intrigue, power, and exile, yet managed to leave behind writings that still speak to modern readers with astonishing clarity. His life embodied the tension between philosophy and politics, wealth and wisdom, action and contemplation. Above all, Seneca taught how to remain calm and rational in a chaotic world.

Check new book – Seneca, His Life and Philosophical Activity

A Life in the Shadow of Power

Seneca was born around 4 BCE in Corduba, Spain, then part of the Roman Empire. His father, Seneca the Elder, was a respected orator and writer. The family was wealthy and well connected, and young Seneca was sent to Rome for education. There he studied rhetoric and philosophy, becoming especially drawn to Stoicism, the Greek school that emphasized reason, virtue, and emotional self-control.

Early in his career, Seneca entered politics and gained a reputation for eloquence. But success brought enemies. Under Emperor Caligula, his talent provoked jealousy, and under Emperor Claudius, he was accused of adultery with the emperor’s niece and sent into exile on the island of Corsica. He spent eight years there, cut off from public life, studying and writing. His letters from exile show a man wrestling with disappointment but also deepening his philosophical understanding.

In 49 CE, Claudius’s new wife Agrippina brought Seneca back to Rome as tutor to her young son Nero. When Nero became emperor at seventeen, Seneca became one of his chief advisers. For a time, he tried to guide the impulsive ruler toward moderation, helping govern the empire with competence and restraint. Yet as Nero’s cruelty and paranoia grew, Seneca withdrew from politics, knowing that his influence was waning. Eventually, he was accused of complicity in a conspiracy and ordered to take his own life in 65 CE. He met death calmly, in the spirit of the philosophy he had preached.

Stoicism in Roman Life

To understand Seneca’s thought, one must understand Stoicism. Founded by Zeno of Citium in Greece, Stoicism taught that happiness comes from living in harmony with nature and reason. External events are beyond our control; what matters is how we respond to them. The Stoic ideal is the wise person who remains unshaken by fortune, pleasure, or pain, who possesses inner freedom even under tyranny.

Seneca made this philosophy practical for the Roman world. Unlike the early Stoics, who lived simply and avoided public life, Seneca was a man of the court. He understood the temptations of wealth and power firsthand. His writings reflect the struggle to apply Stoic principles amid corruption and ambition. He did not claim to be a perfect sage. On the contrary, he admitted his weaknesses and saw philosophy as a remedy for a sick soul rather than a badge of perfection.

Letters to Lucilius

Seneca’s most enduring work is his Letters to Lucilius, a collection of moral essays in the form of correspondence with a younger friend. In them, he discusses friendship, death, anger, poverty, wealth, fear, and the art of living. The tone is personal and reflective rather than systematic. Each letter is an attempt to help Lucilius, and the reader, face life with courage and calm.

A recurring theme in these letters is the shortness of life. Seneca reminds us that time is our most precious possession, yet we waste it as if it were infinite. People guard their property but squander their days. True wisdom, he writes, is learning to live each moment fully and to prepare for death without fear. “It is not that we have a short time to live,” he says, “but that we waste much of it.”

He teaches that death is natural, not an evil. To fear it is irrational, for it cannot be avoided. What matters is not how long we live but how well. Life should be measured by depth of experience, not by years. To live well is to live according to reason, to master desires and emotions so that they no longer dominate the soul.

On the Inner Life

Seneca saw philosophy as medicine for the mind. Human suffering, he believed, arises from false judgments: we think that wealth, status, or pleasure bring happiness, and when we lose them, we despair. But external things are indifferent; they have value only insofar as we use them wisely. The wise person remains content regardless of circumstances because true happiness comes from within.

He often compared philosophy to a guide in a storm. We cannot control the winds of fate, but we can adjust our sails. Virtue, not luck, determines peace of mind. This idea appealed to later thinkers and continues to attract modern readers because it offers stability in a world of uncertainty. Seneca’s calm voice reminds us that while we cannot change what happens, we can always change our attitude toward it.

Anger and Self-Control

One of Seneca’s most famous essays is On Anger, where he analyzes one of the most destructive human emotions. He calls anger temporary madness, a loss of reason that leads people to act against their own nature. Anger arises from unrealistic expectations, from believing that the world should obey our will. To cure it, we must train our minds to accept reality as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Seneca recommends practical methods for controlling anger. Delay your reaction, he says, because time weakens emotion. Examine the causes of your irritation and remind yourself that others act out of ignorance rather than malice. Compassion, not rage, is the rational response. His approach anticipates modern cognitive therapy: change your thoughts, and your emotions will follow.

Wealth, Poverty, and Detachment

Seneca’s wealth has long been a point of controversy. As Nero’s adviser, he accumulated great fortune, leading critics to call him a hypocrite. Yet Seneca addressed this directly. He argued that possession itself is not evil; attachment is. The wise person may enjoy wealth but remains ready to lose it without distress. What matters is not what one owns but how one uses it. He saw wealth as a tool for generosity and service, not indulgence.

In On the Happy Life, he writes that the good life consists not in luxury but in virtue. Pleasure is fleeting, and riches do not free us from fear or sorrow. True contentment comes from simplicity of mind. He praised moderation, self-discipline, and gratitude. Even when living in comfort, he practiced voluntary hardship, eating plain food, sleeping on the ground, to prove that he could live happily with little. Such exercises, he believed, strengthened the soul against future misfortune.

Friendship and Humanity

Seneca viewed friendship as one of the highest goods. A true friend, he said, is another self. Friendship must be based on virtue, not utility or pleasure. Only those who live wisely and honorably can be real friends, because friendship requires trust and moral equality. He rejected the cynical idea that people are motivated only by self-interest. The wise person, he wrote, does good for its own sake, not for reward.

Seneca’s compassion extended beyond individuals to humanity as a whole. He was one of the earliest philosophers to express a sense of universal brotherhood. All humans share reason and belong to one moral community. He advised treating slaves with kindness, reminding masters that fortune could reverse their roles. His humanism, rare in Roman culture, influenced later Christian ethics.

Fate and Freedom

A central Stoic idea in Seneca’s thought is the harmony between fate and freedom. The universe, he believed, is governed by divine reason, or logos. Everything happens according to this rational order. We cannot resist it, but we can choose how to respond. The wise person does not fight destiny but consents to it. “Fate leads the willing and drags the unwilling,” he wrote.

This does not mean passive resignation. Seneca distinguished between external events, which we cannot control, and our inner state, which we can. Freedom lies in the will’s ability to align itself with reason. When we accept the natural order, we live freely because we act in agreement with necessity. This attitude, called amor fati, or love of fate, later inspired thinkers from Marcus Aurelius to Nietzsche.

Tragedy and the Theater of the Mind

Seneca was also a dramatist. His tragedies, based on Greek myths, are filled with passion, revenge, and moral conflict. Though written in rhetorical style for Roman audiences, they reveal his deep psychological insight. The characters are torn by uncontrolled emotions, especially anger and desire. Through them, Seneca illustrates the destructive power of passion and the need for reason’s control.

Some scholars see his tragedies as philosophical allegories. They show what happens when reason fails and human impulses run wild. In this sense, his plays and his philosophical essays complement each other: one warns through argument, the other through emotion. His influence on later European drama, from Shakespeare to Racine, was immense.

The Meaning of Death

Seneca’s calm acceptance of death has made him a symbol of Stoic courage. In On the Shortness of Life and Letters to Lucilius, he teaches that death should not be feared, because it is natural and inevitable. The time before we were born is the same as the time after we die: a peaceful nothingness. To fear it is irrational. Death is not punishment but release. The wise person welcomes it when it comes, knowing that it cannot diminish virtue.

His own death put these ideas to the test. When Nero ordered him to commit suicide, Seneca opened his veins and faced the end with serenity. He spoke calmly to his friends and continued philosophical conversation as his life faded. Accounts of his death, recorded by Tacitus, show him as a man consistent in thought and action. He died as he had lived, teaching by example that reason can triumph over fear.

Philosophy for Daily Life

What makes Seneca enduring is not only his eloquence but his practicality. He wrote not for scholars but for ordinary people trying to live well. His advice remains surprisingly modern. He teaches how to manage time, deal with loss, control anger, and find peace in simplicity. He urges readers to focus on what depends on them and to accept what does not. In an age of anxiety and distraction, his lessons on clarity and moderation feel timeless.

Seneca’s style contributes to his appeal. His sentences are short, clear, and sharp, often ending with a memorable turn of phrase. He writes as a moral guide, not an abstract theorist. His Stoicism is not cold detachment but active compassion. He wanted philosophy to be a living practice, not a luxury of scholars. To him, philosophy was therapy for the soul, a means to achieve inner freedom in a world of instability.

The Criticism of Hypocrisy

Critics have long noted the contradiction between Seneca’s teachings and his political life. How could a man who preached virtue serve a tyrant like Nero? How could a Stoic, who valued simplicity, possess vast wealth? Seneca himself was aware of this tension. In his letters he confesses his struggle to live up to his own ideals. He portrays himself not as a sage but as a patient undergoing treatment. “I am not a wise man,” he writes, “but a lover of wisdom.”

His life illustrates the difficulty of practicing philosophy in politics. He tried to influence Nero toward mercy and justice, but when he failed, he withdrew rather than compromise his conscience. Whether he succeeded or failed is still debated, but his writings show that he saw philosophy as a continual effort, not a final achievement. Hypocrisy, for him, was not the presence of weakness but the denial of it.

Seneca’s Influence

Seneca’s influence reached far beyond his lifetime. Early Christian thinkers admired his moral seriousness and his emphasis on inner virtue. Some even imagined him as a secret Christian, though he remained firmly Stoic. During the Renaissance, his works were rediscovered and praised for their elegant Latin and moral insight. Writers such as Erasmus, Montaigne, and Pascal found in him a guide to ethical living.

In modern times, his ideas have inspired philosophers, psychologists, and self-help authors alike. The Stoic principles of emotional control, resilience, and mindfulness echo through contemporary thought. Seneca’s insistence that happiness depends on the mind’s attitude anticipates modern therapy and existential philosophy. His calm rationality offers an antidote to the turbulence of modern life.

Lessons for Today

Seneca’s message is especially relevant in an age of stress and excess. He teaches that peace is not found in possessions or power but in mastery of the self. We cannot avoid misfortune, but we can choose our response. The practice of reflection, gratitude, and moderation builds resilience. His reminder that time is the most precious resource urges us to live deliberately, to spend our days on what truly matters.

He also reminds us to treat others with patience and understanding. People act out of ignorance and fear, not pure malice. To forgive is to free ourselves from anger. His writings show that strength and kindness are not opposites but partners. A calm mind is not indifferent but capable of greater compassion because it is not ruled by emotion.

The Legacy of Serenity

Seneca’s life was full of contradictions: wealth and simplicity, power and detachment, public service and private contemplation. Yet through it all he remained committed to the Stoic vision of inner freedom. He proved that philosophy can exist not only in classrooms or temples but in the courts of emperors and the hearts of ordinary people. His calm endurance under persecution, his moral clarity, and his willingness to confront death with dignity have made him an enduring example of integrity.

More than two thousand years later, Seneca continues to speak to anyone seeking balance in a restless world. His words remind us that while we cannot command fortune, we can always command ourselves. The storms of life will come, but reason and virtue remain steady anchors. To live as Seneca taught is to cultivate serenity amid struggle, to act justly without expectation, and to find strength in simplicity.

Conclusion

Seneca stands as one of the great moral teachers of history. He lived in an age of violence and decadence, yet he taught moderation, compassion, and self-mastery. His philosophy does not promise escape from hardship but shows how to endure it with grace. He teaches that peace of mind is the reward of reason, and that virtue is the only true wealth.

His life and writings form a single lesson: that the good life depends not on what we have but on how we think. When fortune changes, the wise remain steady because their happiness rests on inner order, not external success. In his calm words we find a path to freedom that begins within. To read Seneca is to encounter not an ancient relic but a timeless guide who speaks across centuries to the human spirit, reminding us that serenity is not escape from the world but victory over it.

Check new book – Seneca, His Life and Philosophical Activity